[ad_1]

Survivors, drifters, and divorcees cross the resurgent wasteland.

goodDrive far enough Entering Texas from the Louisiana border and you will see the ground dry As the earth crumbles to dust, photographer Bryan Schutmaat tells me that strip malls are fading into the rearview mirror. The landscape opened And so the American West began.

Schutmaat has long been fascinated by the Western world. As he toured with punk bands in his teens and early 20s, he felt himself drawn to the region and its open spaces. His new book son of lifeIt records its latest journey through the West in a decade. and features hitchhikers and “street dogs” he meets along the way.

First in a Subaru Forester and Toyota Tacoma pickup truck, Schutmaat will depart from his home in Austin. and drove towards California He will travel from Interstate 10 onto a more segregated two-lane highway. traversing remote areas of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona when he sensed encroachment on the Los Angeles area. He turned around. All told, he spent more than 150 days on the road, many nights sleeping in his car.

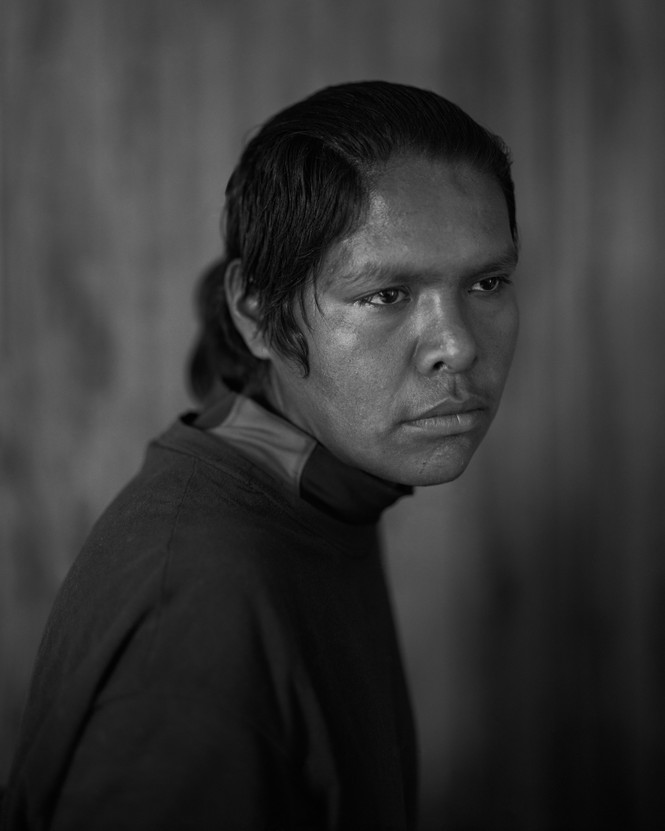

At truck stops and campsites, Schutmaat would photograph people he encountered and offer them crossings from one place to another. Behind the wheel or over a meal or a beer together. He would listen as they told their stories: A man named Tazz hit the road after he was released from prison and tried to find work. He was far removed from his childhood in Maine. and his strong oriental accent contrasts with his surroundings. He claims to have pulled pranks as a child at Stephen King’s house; He later told Schutmaat that he had committed more serious violations. Schutmaat spent hours talking in a New Mexico Denny’s with another man, Walker, a tall traveler with shiny facial hair. Schutmaat took pictures of himself. in the glow of a gas station pavilion, with Walker’s beard blowing in the breeze.

Schutmaat’s work challenges the myths of the West that have long preserved the American imagination. Frederick Jackson Turner theorized that the nation’s democratic culture was built on the peacefulness of the western frontier. Author Wallace Stegner called it This region says It’s called a “geography of hope,” but like Depression-era photographers Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans, Schutmaat makes a vivid vision of the region’s complexity and its promise. It is said that newspaper editor Horace Greeley supports one of his claims: “Go west, young man. Go west and grow with the country.” son of life It makes it clear that in the West there is no guarantee of redemption.

But Chutmaat’s photographs reveal what happens when a country grows old and divided. and its citizens are isolated. Travelers at Chuttamat taking pictures Both widows and drug addicts Migrant workers and survivors homeless people and divorced people They all recovered. But it wasn’t full of hope. In the images of abandoned billboards and ruined cities of Schutmaat, there is no sense that humanity is taming the wilderness. But wilderness that continually reasserts itself over a crumbling human existence.

When Chutamat traveled He would park on the side of the road at dusk and walk up the highway embankment. He set the camera at a high point and left the shutter open for five to ten minutes. through his lens Sets of headlights scattered on the road below melt into a river of light. The road was removed. Wildness returns

These photos appear in Bryan Schutmaat’s new book. son of life–

[ad_2]

Source link